The last time I spoke with the late James Cameron — founder of America's Black Holocaust Museum — he told me how he wished he had volunteers or money to hire help to keep the place open when he was out on the lecture circuit.

That was in January 1996, and I had stopped by for an impromptu visit to the man I had gotten to know quite well back when his museum was housed in a small storefront owned by a mosque I attended on MLK Drive. He lamented that only enough people came by his new location on N. 4th St. for him to keep his utility bills paid.

Age 81 at the time and becoming emotionally drained from being in such high demand — it was, after all, the eve of Black History Month — Cameron was also contemplating what kind of legacy he would leave behind.

"I'm glad there’s a lot of videos and documentaries about me so that, when I’ve passed on, they’ll have something to remember me and the museum by," Cameron told me for an article I wrote for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, where I was an editorial assistant and occasional freelancer at the time. It was my final year as a journalism major at UWM.

"It’s nice if we are able to leave some things," Cameron told me.

Which is why it was so heartwarming for me to visit the new facility in Milwaukee's Bronzeville neighborhood that now houses America’s Black Holocaust Museum. Reopened with funds from a $10 million contribution left by an anonymous donor, the new museum — which covers more than 4,000 square feet — is a welcome sight to an area of the city that has long wrestled with blight and is in desperate need of all the revitalization that it has gotten as of late and more.

I stopped by the museum in late April 2022, more than 26 years after my last talk with Dr. Cameron (as he’s reverently called), and was pleasantly surprised with the museum’s latest iteration.

Unlike the days when the museum was housed in an old fitness center on 4th St. and visitors were likely to encounter a sign on the door that read "Knock Hard," the facade of the new facility beckons traffic and passersby from North Ave.

Once inside and after they pay a modest admission fee, visitors are greeted by images of Dr. Cameron and quotes from various stages of his long and storied life.

"We really wanted to keep the spirit of Dr. Cameron as far as his dedication to chronicling the history of Blacks in America, from pre-captivity to present date," explains Chauntel McKenzie, chief operating officer of the museum.

The photographs and quotes of Dr. Cameron featured throughout the museum are there "because we want anyone that walks in to feel his presence and as though he is moderating his experience for them," she says.

Dr. Cameron's Vision

As someone who knew Dr. Cameron personally — and as one who took several guided tours of his museum back to the late 1980s and early 1990s, when it was located in a small King Drive storefront — I can attest to the fact that Dr. Cameron’s presence as one who survived a lynching and as a historian of the Black experience in America was always the museum’s greatest treasure.

The museum was never really big on artifacts. In fact, an old Ku Klux Klan robe is about the only artifact that I remember. Mostly the walls were bedecked with blown up newspaper articles and photographs of horrific events like the lynching that Dr. Cameron narrowly escaped in Marion, Indiana, in 1930.

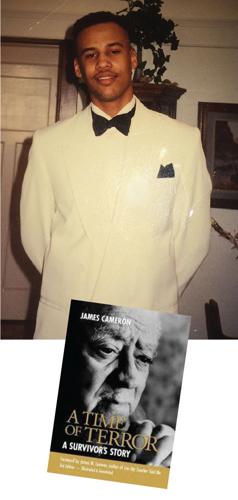

What drew me to the museum time and time again was not the physical items or images that the museum housed. Rather, it was the lively way that Dr. Cameron engaged his visitors with the story of his life, which was originally told in the 1982 book "A Time of Terror: The true story by the third victim of this lynching in the North who missed his appointment with death."

Dr. Cameron once revealed to me that he took some artistic liberties with the book cover, which shows two of his friends — Thomas Shipp, 18, and Shipp's friend Abe Smith, 19 — hanging from a tree after they had robbed and killed a white couple in Marion.

While the book cover shows an empty noose in between Thomas and Abe, Cameron told me he had an artist insert a third noose into the picture to illustrate what the mob had intended to do to him that night in 1930 before he was miraculously spared when someone in the crowd stated that he had nothing to do with the crime. He was only 16 at the time.

As an aspiring journalist and a purist when it comes to history, I didn’t see the need to fabricate the image of the third noose. The blood-curdling picture of those lifeless Black bodies hanging from a tree as a white mob looked on — seemingly proud of what they had done — was shocking enough.

But as a marketing ploy to make an already sensational story even more sensational, perhaps this creative license can be forgiven and overlooked.

From A Book To A Museum

Cameron’s book is actually what enabled him to secure the first space for his museum in a storefront on the corner of N. King Drive and W. Wright St. The building is still controlled to this day by Masjid Sultan Muhammad, a mosque that traces its origin back to the Nation of Islam, a Black separatist group which, ironically, was born the same year as Cameron’s near-lynching experience.

An elder from Masjid Sultan Muhammad, which I first attended as a teen growing up in Milwaukee, told me that he first purchased Cameron’s book at Positive Image, a now-defunct Black bookstore once located in the Sherman Park neighborhood where I grew up. I used to frequent the bookstore myself.

"They were selling his book, and saw he's in Milwaukee," the elder recalled of Cameron. "I located him just to meet him and get his story. We talked, and he said he wanted to do the museum but couldn’t find anyone who would rent him space.

"I told him we had the Clara Muhammad School. I brought it to the community and everyone agreed that we could house him in the school."

That Cameron’s museum would find its first home with a mosque that originated from the Nation of Islam is hardly surprising.

The Honorable Elijah Muhammad, a co-founder of the Nation of Islam, spoke of how he had narrowly missed seeing a lynching as young boy in Cordele, Georgia. Several accounts, including a book by Karl Evanzz, say the victim in that case (which took place in 1912) was Elijah Muhammad’s childhood friend, Albert Hamilton, who had been falsely accused of raping a white woman.

Wrote Evanzz:

After the rope was secured around the trunk of a tree, hundreds in the mob aimed their rifles and shotguns at the dangling, dying youth. By the time the smoke cleared, Hamilton had been shot more than 300 times. As the mob proudly dispersed, an amateur photographer snapped pictures of the mutilated victim, and then ran excitedly to the local camera shop and had the most gruesome photograph made into a postcard.

Hamilton's name is one of many on a website for America’s Black Holocaust Museum that honors those who died in lynchings. Elijah Muhammad said the incident left an indelible imprint and played an essential role in his gospel of Black separatism.

"I looked at this sight, swinging," Muhammad says in a video clip in which his protege Malcolm X is seated in the background. "And I said — with tears in my eyes, because I knew the young man — if there's a God in heaven, I pray that he grew [sic] me up and make me strong enough to get my people out from their enemies."

The elder who appealed for the mosque to house Cameron’s museum told me that even though the community had been moving away from Elijah Muhammad's Black separatist teachings in the 1980s, they still had an interest in preserving the history of America’s racist past.

"When you tap into the rage, that was part of a strategy to get Black people to come to action to keep reminding them of the fight," the elder explained.

So housing Cameron’s museum at the mosque’s King Drive storefront was a no-brainer. The museum was a natural fit. The mosque originally housed the museum in its school, but then gave him the King Drive storefront for a nominal fee. I know because when I became the mosque treasurer, I used to collect the rent.

The Museum Develops

It was there at the King Drive storefront that I first met Dr. Cameron. I can't quite remember if I saw his museum after I joined the mosque, or if I noticed it one day on the No. 19 bus on my way to work downtown as a janitor and became intrigued by the sign that said "America’s Black Holocaust Museum."

I was especially interested in Black history at the time because — as a teenager influenced by the combatant music of Public Enemy and the fiery oratory of Malcolm X — I was in the midst of one of the more militant phases of my life. At the time I wrote a column for my school newspaper under the name Jason X.

I remember enjoying Dr. Cameron’s tours so much that I took my girlfriend at the time to tour the museum before we went to dinner at The Ja'Stacy.

Dr. Cameron made us feel like a couple. He treated Crystal with the utmost respect, inviting her to "step this way" as he led us on the tour.

He told us his life story. He spoke of his time in prison, where he was sent for five years after being convicted as "an accessory to the murder that incited the lynching," as the museum’s website states. He reminisced on how it was the Book of Psalms that brought him so much comfort while he was serving time. His fondness for the psalms was so passionate that it made me want to read a few myself, even though as a new convert to Islam I was more devoted to the study of the Qur'an.

He gave us history lessons on the TransAtlantic slave trade, a topic of interest to Crystal. He often noted that as Africans in captivity were placed into the hulls of slave ships, they lost whatever status they might have had in Africa — even if they came from royalty — and arrived in America as property.

Dr. Cameron’s lessons represented the kind of education that Crystal and I were not apt to get in Milwaukee Public Schools, and which I suspect most public school students are still not getting to this day. That’s one reason I was delighted to hear that schoolchildren represent the biggest segment of visitors to America's Black Holocaust Museum.

"This is really important to us, especially when young people come here," McKenzie told me of a wall in the museum that features Black history that stretches back millenia.

"We start here because as far as science has been able to prove, the first signs of life that they could find anywhere on earth have been in Africa," McKenzie says. "We show this because it's important for everyone to see, regardless of where your ancestors migrated to throughout the earth, that so far today the only signs of civilization are right here in Africa, which is why it's considered the cradle of life."

The graphs at the museum that show what happened "pre-captivity" are meant to "debunk that misnomer that we were this uncivilized race of people that needed to be saved, that were savages," McKenzie says.

While much of the museum is dedicated to showing the horrors of slavery and the lynchings that followed in the era of Jim Crow, a fair amount is also devoted to Black monarchs such as Mansa Musa, thought to be the richest man in the world at the time of his reign over the Mali empire in the 1300s.

There are also depictions of Black civilizations in ancient Egypt. "This is a really important piece, because what we hope it shows for anyone that doesn’t realize it is that we were mathematicians and engineers and building pyramids that to this day people have not been able to figure out how to reconstruct," McKenzie says.

During my recent tour, I mentioned to McKenzie how much of this Black history I learned not in school but from a book titled "Before the Mayflower: A History of the Negro in America, 1619-1962," a tattered copy of which I bought from a fellow student at Marshall High School for $10 (and is still on my bookshelf).

"That’s what we hope that this exhibit does,” McKenzie says. "I love when we have young people stopping in here."

School teachers are putting entire classes on county buses to visit the museum. "It just warms our hearts," she says. "I drop everything I'm doing when they come, because they’re here to pay admission and that was Dr. Cameron’s spirit to everybody that walked in. He was here to tell the story and walk them through."

And even though he passed away in 2006, Dr. Cameron is still here to guide visitors through his museum, just like he was when I first discovered the museum several decades ago in a small storefront on King Drive. MKE

Jamaal Abdul-Alim is a Milwaukee native and longtime journalist who currently resides in Washington, D.C. He began his journalism career as a crime reporter at the old Milwaukee Sentinel and later joined the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. In his free time, he enjoys bike riding and playing chess.